I’ve launched a new venture fund investing in unruly founders. Read the launch manifesto here!

Category: Venture capital

On seed rounds valuations

Valuations on seed rounds are a timeless debate.

Every 6 months at YC Demo Day time the debate gets reignited given the average YC company raises at a pretty vertiginous valuation.

As usual, a tweet sparked it all:

Ilan introduces the debate from the founder’s perspective: if you are raising a seed round at a $15-20M cap (which if pre-money, means a $25+ post most of the time), Ilan’s argument is that it dramatically increases the difficulty of raising a Series A or Seed extension at a higher valuation.

Should you maximize the valuation when raising a seed round?

That’s the question every founder asks himself. Well, not everyone: some just go straight for the highest val possible.

There is a whole LOT of advice online, but the survivorship bias present in all of the advice received from both founders and investors doesn’t really help making the decision.

The way I like to think about it is in the framework of upside maximization and downside minimization.

If everything goes amazingly with your company and product during the seed phase, then obviously having maximized the valuation will result in the lowest possible dilution.

But, if things don’t go that well, and let’s face it – things never go that well, and the road to Series A will be a tad longer, then having a super high val starts to become a truly existential issue for the company.

I’ve raised two seed rounds on the entrepreneurial side, both very large and both at steep valuations, and I’ve regretted both of them.

Raising 2.5-3M on a $15M cap, means that you’re already at a $18M post. If it takes you a bit longer to find product market fit or prove the metrics that are needed for a Series A, then you’ll have to do a seed extension (second seed, seed +, bridge, whatever your preferred naming is) – and things get ugly very fast there, for both the entrepreneur and the investor.

So at that point you have three choices:

- Extend the seed at the same valuation. This sounds easy enough but there’s a number of problems:

- raising at the same valuation of 2 years prior is never a great sign, for previous nor prospective investors

- the dilution hit will be significant, as it’s essentially doubling the amount of the initial seed raise

- and on top of that, a $18-20M post is still steep for a company that hasn’t proven itself!

- Raising at a lower valuation: this is basically a no-go

- Swinging for the fences and trying to do a seed+ at a slightly higher valuation:

- not everyone will be able to achieve this

- the problems of the first point all mostly stand, especially the new even steeper val

Note: YC has recently introduced post-money SAFEs which should solve this aspect, but the point on dilution stands.

So essentially as a founder, you have a bit of extra equity to gain if all goes well, but you’re essentially gambling the company away for it, because if something doesn’t go to plan, those three options up here aren’t all that desirable.

Should you care about pricing when investing?

Soon into the debate, Garry Tan weirdly enough missed the whole point of it all and switched it completely towards the investors side.

Felt really weird, but now we’re here. And pricing is one of the most interesting debates going on in venture investing – and one where you usually find two very opposite camps.

The argument for price insensitivity

As you can see, the YC camp is firmly in the “price doesn’t matter” camp. For the YC-school thinkers, the power laws of venture capital make it so that getting into the right company at a high price will dwarf the returns of getting into an average company at the right price.

Essentially, the only thing you should really care is finding, and getting into that unicorn.

They make it sound like it’s the most obvious thing, but the reality is way more nuanced.

The first thing to realize are the incentives: YC, until recently, used to get a ridiculous $300k post valuation (they invested 20k for 6.06% common stock, and the $100k at $10M post for 1% actually came from a YCVC fund with other investors). (I don’t know the structure of the new $150k deal).

And then, when you look, the people that tell you this, all got into their best deals at extremely cheap pricing. The first round for Twitter, Uber and so on, where all on single-digit post valuations, something that rarely even happens again now.

But the argument usually goes: getting into Uber at $5 post or $20 post doesn’t really matter, the important is getting it.

But the reality is that it does matter. The difference is a 4x return.

Some quick venture math

So say that you have a $30M fund ($25M investable after fees, 20 $500k checks and $15M follow ons)

Your $500k check. At $5M post, you’re getting a solid 10% of a company. At $20M post, you’re getting 2.5%.

Skipping pro-rata math for simplicity, and assuming a solid 70% dilution before exit (option pools and other investors do take a lot of space on the cap-table), you will be left with a 3% or .75% depending on the post valuation you invested in.

This means, that to return your fund twice over, the first investment requires a $1B exit, and the second one a whooping $4B. A $15M difference in cap at seed means $3B plus in difference at exit (or $30B, if we’re talking about a $10B vs $40B exit).

This simple math makes it clear to me that both camps are right: if you get an Uber / [insert other ginormous decacorn here] then you will be just fine.

But it’s also clear that raising the post-val meaningfully raises the stakes.

First of all, even in a decacorn-like situation, you’re returning a fraction of the capital you would have at a lower valuation.

But more importantly: not everyone will get a decacorn in their portfolio.

Imagine getting a company you backed at the seed round with one of the leading seed checks in the deal achieve a $1B exit (and there are only 10-20 every year in the US), which would make you one of the top investors in the country, but returning just a quarter of your fund on it. ($1B*.75% = $7.5M)

In my book, that would be a pretty miserable failure.

So: if you are extremely confident that you will find your decacorn, then by all means, investing at $20M pre is fair game. But, if like most investors, you think that already finding one $Billion dollar outcome in your fund would be a success, then being disciplined on pricing is a must-have attitude.

The accelerating pace of innovation and what it means for startup investors

We’re living in the most innovative and fascinating period of history

I’ve had this nagging feeling for a while.

I didn’t really know what it was, but it surely had to do with the insane scale of amazing new fields and opportunities that I have an interest in.

I find it hard to keep track of everything and especially to become an expert in any of those fields.

And then I succumbed to the idea that the acceleration of commercial-ready technology is just unmanageable for a single individual.

When the internet first showed up, it was really (I think) the only massively disruptive technology to show up after the transistor/computer.

But now, we live in the most exciting period of human and technological history and our progress is accelerating so fast, fueled obviously by the internet’s orgy of ideas, that so many more technologies have reached the phase where they can be deployed commercially and have the potential to change things as much as the internet itself.

This means that for every new sector, there is a specific community getting formed with people who are dedicating their life’s work to that specific field and developing deep insights and experience.

At the same time, there are innumerable startups being born in every field, and (from what I can remember) this represents a couple orders of magnitude more than the number of early startups in the internet, even compared to just 8–10 years ago.

With Mission and Market we’ve been lucky to invest in many of these sectors and I’ve been fortunate lately to have the time to study more in depth some of them. And to me, each one of the fields I list below represents an unmeasurable amount of opportunities.

But my brain is now tied in this constant dilemma, and I think it’s one that every VC or angel will have to come to terms with at some point:

should I try to keep track of all of it or should I just choose one and focus on that?

I don’t really have an answer yet, and for now I’m trying to keep my interest open to all of them (and new ones that keep on showing up!) but I’m not sure how long I’ll be able to continue doing that.

This goes back to the rise of the thematic / vertical VC fund, which I wrote about 3 years ago (oh man, time flies).

I think we’ll end up seeing even more of these funds and I think they will produce very decent if not above-average returns, given that now each vertical has the potential for multiple breakthrough companies.

Another point to briefly touch on is the value-add a generalist investor like myself could ever hope to bring to a very specific company in a new field.

Ron Conway and others have been made famous by their decision to focus exclusively on internet investing in the very early days (and have been awesomely rewarded for that), but now there are 10 new internet-like fields.

Will everyone who focused on one be rewarded like them? Will one field completely outdo all the others? Will investors just have to embrace all of them?

These are the questions that keep me up at night, and I hope to discuss them with many of you.

$(X) is the new internet

This is my personal list of fields that I think have a similar impact potential to the internet. It doesn’t take into consideration fields which I think have massive opportunity but not to that scale (eg. cybersecurity) or some that have already demonstrated that (eg. mobile) or some on which the jury is still out (eg. cleantech, which probably merits a discussion of its own).

Deep Learning is the new internet

The things that we’ve been able to achieve with deep learning in just a few years have been astonishing. For me, it’s definitely the most interesting part of machine intelligence.

Deep learning changes everything. It enables us to spot answers to questions that we dare not even ask just a few years ago and also create things which would have been impossible just a few months ago.

If we add other aspects of machine learning and, specifically, generative AI — the mind is blown away at every single new piece of information I gather on the space.

We’ve been fortunate to invest in Atomwise (finding new drugs thanks to DL), Enlitic (spotting lung cancer with DL) and Floyd (making it easier to run DL processes) — but there are SOOO many more that I’d like to be involved in and SOOO many more I’ve never even heard about.

I’ve also invested in a Deep Learning-specific venture fund with which I hope to get more exposure to the space — but I think DL will be so pervasive that I can never get enough exposure.

Blockchain is the new internet

I’ve recently seen a tweet by Joel Monegro of USV which clearly encapsulates my own thinking.

Web is boring. Blockchain is interesting.

— Joel Monégro (@jmonegro) March 11, 2017

The blockchain is really the first major disruptive computer science technology to come around that was entirely unexpected and has the potential to change everything.

I’ve been fortunate to know about Bitcoin since early 2011 (less fortunate to turn off my mining machine right after as it was about to boil) and have been following the space ever seen.

I now own a dozen different cryptocurrencies and have read probably triple that in whitepapers describing different decentralized applications (dApps) and currencies.

I’ve made (digital) money on some and lost (real) money on others, but the level of experimentation and excitement that is seen in the blockchain space and community in unrivaled.

Many paradigms are being completely redefined by blockchain technology. Decentralization is a really big force and I can’t seem to see an end to its advancement.

Finance, healthcare, manufacturing and more industries will ask themselves how they operated without the blockchain — just as we ask ourselves today how we operated without the internet.

Synthetic biology is the new internet

The amount of innovation happening in synbio is astounding. It is finally all within reach of “normal” entrepreneurs and outside of big University research labs.

We’ve been lucky to look at many deals in the space and even invest in some.

It is abundantly clear that the future will be powered by synthetic biology. So many aspects of it that we can’t even imagine.

Materials will all be fermented or grown, as will all sort of different food elements, especially animal-based food.

It will seem just absurd that we were wasting the Earth’s resources as well as breeding and killing billions of animals every year.

The economic value of old-school industrial production that is being impacted is incalculable and we will see the new Rockefellers in this field.

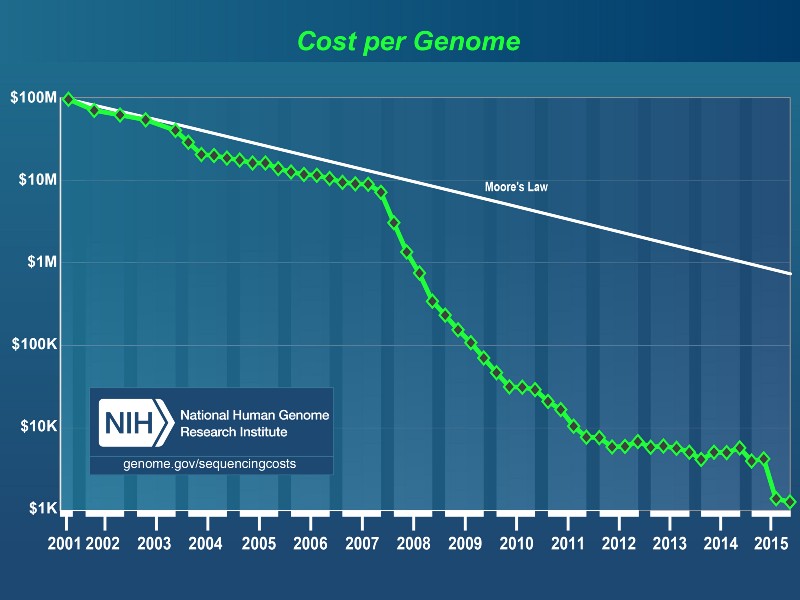

Genomics (and microbiomes) is the new internet

This image should make everyone insanely excited. For the first time in history we’ll be able to understand how we’re made and why we do some of the amazing things our bodies make us do.

With RNA sequencing, and microbiome understanding, we can even monitor our bodies responses in real-time to various diseases and drugs. We’re investors in the pioneering RNA sequencing company and we’ve seen the future. It is amazing.

But it doesn’t stop at understanding.

With CRISPR-Cas9 we can actually change our DNA and impart new instructions. This is just mind-blowing. We’ve been small investors in Caribou Biosciences (thanks AngelList!) and we feel like we’re watching the future unfold.

The advances being enabled by CRISPR are still pretty incomprehensible but we are seeing more and more entrepreneurs using this tool, as well as developing parallel tools (DNA cell delivery, etc.).

It’s a new world.

Robotics is the new internet

We’ve all seen Boston Dynamics’ videos of their andro-dogoids and we’ve all been amazed / scared.

The reality is that robotics is today way more advanced than we thought. Just walk in a factory anywhere in Europe and you’ll see robotic arms and other autonomous systems.

Slowly we’re automatic all the repetitive tasks.

We routinely see videos of cars and trucks being driven by themselves.

Autonomous hardware systems are beginning to become a whole new sector with a vast amount of applications (and already many $B exits).

As software and materials become cheaper, we’re going to see many more of these companies. And when we’ll have billions of robots deployed, the opportunities for companies will be endless.

IoT is the new internet

I haven’t followed the IoT revolution as much as I wanted, but it does feel like another field which is slowly becoming a massive platform and opportunity.

I don’t think we can really understand the impact of receiving data from and being able to interact with trillions of objects in real time.

Unsexy maybe, but still revolutionary.

Voice technology is the new internet

Most of you will have an Alexa in the house by this time. We have a Google Home and even if it’s not loved by all, conversational software enables a host of new use cases and thus many new potential companies.

It feels like this is a game reserved for the big ones, but I believe there will be a wide interest from startups and we’ll see some tools that will become comparable to our best friends in the future.

Voice, like all the other areas listed here, is a completely new platform — and will see very specific apps that couldn’t be built anywhere else.

3D Printing is the new internet

3D Printing is yet another completely different area that is a platform onto itself.

It basically brings all of the advantages of the internet to physical things.

Sure, it might still be very early, but the potential is clear and massive. I think it’s really incalculable.

The ripple effects of a usable and economical 3D Printing revolution would change the world as we know it, and enable a myriad new companies.

VR/AR is the new internet

I truly think that in the next years we will spend as much time in VR as in the RW.

We’ve already seen the first few $B exits in this space and it’s just the beginning.

The promise of companies such as Magic Leap just compound this even more.

I think in 15 years we will not have computer screens anymore and will think that they were the most limiting aspect of modern life.

“Do you remember when you could only see what was on your small little screen? LOL”

Clearly opening up a new world, opens up a whole new economic paradigm too. We need everything new in VR. Operating Systems, networks, games, productivity tools, and even more of what we can do today on the internet. Sure some will be just moved over by internet companies, but many VR-native companies well be born — and they will be huge.

We can see this thanks to our investments in FOVE and Limitless, which is redefining how we create experiences in a VR-native fashion.

What am I missing?

I’m sure there are a few other fringe areas that have the potential to be platforms of massive change (microfluidics? nanotech? alternative currencies?).

Let me know where I should be looking at 🙂

Thanks to Yannick Roux for reading a draft of this post.

The 26 most innovative venture capital firms

A look at who’s innovating the business of funding innovation

Every new VC firm that launches touts to be a “new breed of venture capital firm”, but the reality is that most of the time it’s just a straight up old-school VC model.

That being said, VC has seen some massive innovation in the past decade: the rise of the super angels, the subsequent explosion of seed funds, VC blogging, AngelList — today the fundraising environment is certainly different for founders.

As I’m thinking through how to approach investing in Europe (I’ve just moved back here), I started to recall and research the most innovative VC firms and models that I’ve seen in the past years.

Here you can find a list of firms that I think brought the most innovation to the VC landscape in recent times. I’m sure that I’m missing a bunch more, so feel free to tweet me some more and I’ll add them.

Disclaimer: My small investment firm, Mission and Market, is an investor in a number of companies that received prior or further financing by many of the VC firms mentioned in this piece. I try to mention those in the details, but I’m surely biased even only for my knowledge of these firms’ existence.

I know the recommend button is all the way down, but if you think this is interesting, I’d appreciate a click 🙂

In no particular order:

Correlation Ventures

Correlation Ventures was the first fund to be marketed with the data angle.

I think their strategy is pretty smart, and surely new: they aim to be the dream co-investor for teams looking to fill out a round.

They use analytics and get to a decision in less than two weeks, which is impressive — as their portfolio is, given they’ve made more than 160 investments.

They’re investing out of their second $188M fund (the first was $166M).

AngelList’s Syndicates + Maiden Lane

AngelList has completely changed the early stage investing world, plain and simple.

From intros, to profiles (I use AngelList more than LinkedIn nowadays) and now syndicates it continues to innovate like no other in the venture space.

In particular, Syndicates are the stuff of the future. I’ve been investing in Syndicates sporadically but I’m just stunned at the quality of the stuff I get to see. It’s certainly not perfect at all at the moment, but if you want to innovate this is the price to pay — and I’m sure it will become so in the future.

On top of this, Naval is truly an extraordinary brain and person. Everyone who had the chance to interact with him knows how sharp and kind he is. He’s always been very generous of his time with me.

One of their most recent efforts which had everyone pretty stunned was the announcement of a syndicates-only fund.

This is pretty bold. It’s basically saying that the concept of “proprietary” deal flow is outdated and that by using AngelList anyone can create a well-performing venture fund. The implications of this are hard to fathom, but if you take a look at their portfolio I’m sure you’ll be impressed.

Lots to think about.

Flight Ventures

Gil Pencina is one of the best angels around, having invested in every single major tech company — and he’s also one of the first to have spotted that Syndicates are probably the future of early-stage investing. I deeply respect him for this.

Gil wants Flight.vc to become the Fidelity of startup investing. You choose the vertical, theme or location and Gil will have a syndicate for you to back.

He recruits managers for each syndicate, which do all the work and then he helps them by reviewing the deals and, most importantly maybe, getting the money to flow.

I’m now also an investor in one of his new funds (devoted to deep learning in this case), which are evolving the model even further.

SignalFire

I had the pleasure of meeting Chris in 2013, just after he left General Catalyst and was impressed with his very ambitious vision.

Chris rightly observed that for an industry that is constantly immersed in software, it has used very little of it to innovate. So he set out to create a firm that uses a lot of software to spot investment opportunities as well as help out its companies.

Its software tracks talent and can be used to spot people that are about to start companies as well as help its portfolio companies hire top talent, which is often the #1 problem for companies that need to grow fast.

Signalfire also has a distributed model where top people in Silicon Valley actively help the portfolio companies, and in exchange get access to the software (and I guess better economics on the fund as LPs).

They raised a first $53M fund and should be just about done raising its second $300–350M fund.

Deep Knowledge Ventures

DKV is another pretty futuristic firm that touts its use of data as a competitive advantage. They use a software created by a 3rd-party company called VITAL to spot investment opportunities (mainly in the life sciences sector) — they even named the algorithm to the board in a PR move.

They have launched a specific Life Science fund and are about to launch a new Digital Capital fund focused on BTC, blockchain, AI, data, etc.

Not much else available about them unfortunately.

Tusk Ventures

Tusk recently participated in the A and B rounds of one of our portfolio companies, and I couldn’t be happier.

They’ve developed a brand in Silicon Valley for helping companies navigate hard and uncertain regulatory terrain, which in this case were the #1 risk for the company — having a dedicated team for that makes you a bit more comfortable.

Tusk Ventures gets some serious equity for their work (they also now have a fund, and I don’t know if they invested cash or services) which is oftentimes very lucrative for them, given their first client was Uber.

There have been a lot of work-for-equity schemes around obviously, but I specifically like this one because it is a very scarce skill-set that can actually command equity from top startups (vs say a design firm, of which there are a ton and for which top startups would just pay cash).

Redstone Digital

These guys are sharp. I’ve found them randomly only but I’m impressed with their model.

Redstone basically offers a “VC-as-a-Service” model to big corporates or other type of LPs.

So, instead of saying: “give me your money and we’ll see in 10 years how good we were at managing it” they’re going to these huge institutions and telling them “hey, why don’t you build your own corporate venture fund? we’ll do it for you, but it’ll still be yours”.

That’s a massive value proposition to companies that want to dip their toes in the corporate VC world, but have no idea where to get started and also want to be in control of what they invest.

In this way, Redstone is able to build a massive AUM base for which I imagine they get both fees and carry in a shorter amount of time — while having access to the corporates firepower.

Some conflicts of interest for sure, but if managed correctly this could be a very solid business

Kima Ventures

Kima is a hybrid French / Israeli firm, which in its short existence (6 years) has invested in more than 400 companies.

They do so by moving extremely fast and making investments as often as 2–3 times per week. They invest globally which helps widen the funnel.

The team is distributed and I had the chance to recently meet with Vincent, their partner in London.

On top of being extremely entrepreneur friendly in their speed, they have also built a first in the VC world, a status tracker for their evaluation of a deal: https://status.kimaventures.com/

500 Startups

Dave McClure certainly needs no introduction as well, but his work with 500 can’t be looked over.

Dave has pioneered the high-frequency “index” model of startup investing, with the belief that investors can’t really pick the winner so the best way to invest is to just invest in a whole lot of companies and then follow-on on the best ones.

This approach has made him quite a few enemies in the valley, and didn’t give him a very easy time while in LPs boardrooms (maybe paired with his unorthodox clothing, language and methods) — but I think the numbers will show his acumen in the long run.

I’ve had the chance to shadow Dave for a few weeks back in 2011, and have been extremely impressed by his vision and ambition.

In the time that passed, he has been launching vertical-local funds all over the world given his other thesis that the next big unicorns will be founded all around the world — and he’ll be there first to get a shot at all of them.

Y Combinator

YC has probably had the most impact on the venture scene in the last decade than anything else.

I’ve been fortunate to participate in a YC batch with my company to see what the hype is all about.

Jessica and Paul are true visionaries, and with the ambition of Sam YC is not really stopping for a moment.

It’s crazy to think that when they first launched, there was no early stage acceleration program for startups — with the millions that exist today — but it was really thanks to them that all of this movement was born and that so many people now are even aware of entrepreneurship as an avenue for their future.

SOSV

I’ve gotten to know the guys at SOSV through their Indie.bio program which is run in SF by Ryan and have been extremely impressed with their approach.

They create a number of vertical accelerators and exclusively fund all operations and investments, plus they have a core fund that follows on on the best graduates.

This gets all of the benefits of the vertical approach (high value add, good screening capacity, great deal flow), with the diversification of different verticals.

We’ve invested in two of their companies and are looking forward to finding even more.

They tout $250M AUM, 500 startups and a solid 30% net IRR.

You should read the fascinating story of the founder.

Entrepreneur First

I can’t recall the amount of times that, while chatting with people about what to do next, I got suggested to look at Entrepreneur First as one of the coolest new models around.

EF is a pre-idea entrepreneurship program. They take the brightest young minds from the top universities in the UK (and abroad) and help them meet other people and launch a startup.

I’ve always seen two major risks to this approach: 1) inexperienced just-out-of-school people, which can be great for social software, but probably a bit less so for hard-tech B2B companies and 2) co-founder mismatches and problems, given you’re literally meeting your co-founder for the first time at the program.

But they seem to have solved for both risks: on top of recent graduates, they are now targeting people coming from Tier 1 companies, and they say they have developed a great program to match people.

The results have certainly been brilliant, given Twitter has bought up one of their companies for $150M, and the others are not doing to bad either.

Indie.vc

Indie.vc is the grand experiment in alternative funding model for startups by Bryce Roberts, a partner at OATV.

He’s questioning the assumption that startups need only to focus on hyper-growth and not on just creating a sustainable, profitable business. Thus, indie.vc has a model where it will get paid back by dividends from the company, specifically it will get 80% until it gets paid 2x and then 20% until it reaches a hard cap of 5x its investment.

Meanwhile, should the company decide to actually go for hyper-growth and raise additional funds, its investment will just turn to equity at a pre-negotiated conversion price.

My view here is that this is an awesome and very much needed experiment. Indie.vc thus will have a portfolio of a few companies that will raise more money where it will get equity and have a potential 5x return from the ones that don’t. Given this approach would tend to find companies that are inherently less risky, it might yield a pretty interesting return.

They’re now on their v2, raised a specific fund and make $100k-500k investments.

Best of luck to Bryce on this amazing effort.

Lighter Capital

Lighter Capital is not really a VC fund per se, but actually a VC-funded startup. They raised $17M for their operations, and invest out of a $120M LP pool.

Lighter provides revenue-based financing to SaaS businesses. That means that you get a check for say $100k, and have to pay them back a multiple of that amount, and such payments come out of your revenues — the more you grow, the more you pay.

They write checks of up to ⅓ of a company’s annualized revenues and don’t get any equity.

This is an extremely smart model, which drives probably around 30% annual returns with much lower risk than what VCs have.

Lighter Capital is able to use a lot of data and metrics to project revenues and is completely uninterested in the final outcome of the company, they are just very aligned in the short term to help it grow fast (so that they get paid back earlier, and thus generate better IRR).

A solid solution for people who don’t really want to give away equity but have a solid business and could use a boost.

Bullpen Capital

I had the pleasure of meeting Paul and Duncan from Bullpen after they invested in a company I worked at — and remember being instantly impressed with them.

They were the firsts to aggressively go after a clear opportunity in the VC market: the famous “Series A” crunch.

Bullpen figured out that with the massive explosion of seed funds (themselves pretty innovative at the time), and the shrinking of the later stage VCs post-bubble, there was now a massive opportunity to find underpriced post-seed deals.

They have been thus able to invest in companies that needed just a bit more time before raising their Series A, but whose seed-round VCs wouldn’t bridge. This means getting companies that are fairly de-risked but still very cheap.

It looks like it’s going well for them as they’re already on to their third $75M fund (the previous ones were $24M and $31M).

I also highly suggest listening to Paul’s interview with Harry Stebbings on the 20minVC.

Data Collective

If you know Matt, you already know he’s the man. Add Zack to the mix and you get one of the best new firms around.

DCVC’s innovation stems surely for its approach to backing extremely deep tech, but also from employing a “collective” approach of giving experts (LPs and not) meaningful carry in exchange for their help vetting and helping its portfolio companies.

These are solid people, and include DCVC’s equity partners include Jawbone’s VP of Data Monica Rogati, Facebook’s and now Google’s head of analytics Ken Rudin and Factual founder Gil Elbaz.

What I particularly like about DCVC is that they get all the marketing and operational advantages of having a “vertical” fund (focused on data advantages), and are able to still be extremely broad in the target markets.

They are now investing their fourth core fund, of $177M, with previous funds having been $140 Fund III, $75–100M Fund II and $6m Fund I.

They also have two $125M opportunity funds.

We are investors in 3 deals where Matt and Zack invested, and have also been honored to receive a small check from DCVC in my company’s seed round so I might be biased, but think there are few funds of this quality around.

Another great 20minVC episode to listen to.

Upside Partnership

Kent Goldman was exposed to innovation in VC early on, being a principal and then a partner at First Round Capital — one of the great early innovators of the seed model (almost 12 years ago!).

When he left and decided to start a new firm, he took a spin on the model and made every single entrepreneur he invests a carry holder.

That should ideally foster a deeper sense of community and shared goals between all of the portfolio founders.

The percentage of carry reserved to founders is probably around 20–40%. The first fund is a $35M vehicle.

Many firms have entrepreneur or exchange funds, but I think this is the first of its kind.

I don’t know Kent, but we’re co-investors in a deal that I like a lot, so I hope he does really well 😀

Foundry Group Next

Brad Feld obviously needs no introductions and his leadership in the changing tides of VCs, with the new breed of “blogging VCs”, has been impressive to watch.

Recently Foundry Group raised a “Next” vehicle which enables Foundry to invest in later stages rounds of its own portfolio companies (like a traditional opportunity fund), invest in other VC firms (like a fund of funds) and invest in later stages deals coming out of these other firms and the broader network.

Very cool stuff. Brad clearly has seen the benefits of his huge efforts of helping other people and institutionalizing his efforts by raising a hybrid fund such as this one are a really cool and creative move.

Andreessen Horowitz

Rising from a brand-new firm to the top 3 in the world in half a decade is just unheard of, and yet this is exactly what A16Z did.

Aside from the brilliance and power of Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, which would probably have made them Tier-1 VCs anyways, what was most impressive to see was their rethinking of the VC model.

When you visit the A16Z offices, it doesn’t feel at all like you’re in a VC firm (even if they kept the old tradition of being on Sand Hill Road..). Their goal is to model the firm after a creative agency, and employing more than 100 people it seems like they’re commit to it.

The DAO

One of the most ambitious and revolutionary projects in recent memory, the DAO raised more than $100M in Ethereum to build a decentralized venture fund.

It then famously collapsed under a hack which found some loopholes in the code, but it still made a lot of people think about the possibilities that blockchain technology introduces in the venture capital space.

Cota Capital

I wanted to include Cota, a not-so-well-known SF-based VC fund, because of their smart approach to long-term investing and structuring.

Cota is the “union” of the efforts from Ullas Naik (Streamlined Ventures) and Bobby Yazdani (Signatures Capital).

I got to know them as they invested in my company and learned that they decided to structure their vehicle as a hedge fund (as evidenced by their SEC Form D).

This enables them to have a longer term horizon, and be a great alternative for LPs who like to have more flexibility with their capital and can’t commit for a long period of time.

Draper Esprit

One of the many vehicles tied to Tim Draper, Esprit (which was formerly called DFJ Esprit) is innovative in the fact that it actually IPOed on the London stock exchange.

This allows the firm to not be bound by the traditional 10 years fund lifecycle and supposedly have a longer horizon for its investments, consequently enabling them to make bolder bets.

It’s certainly an interesting model, with a bunch of pros and cons, and I’m really curious to see how it goes for them.

137 Ventures

137 is focused on investing in late stage companies by acquiring employee’s shares or lending against them. This is super smart as they get access to some extremely proven companies, at lower-than-market valuation, and can do so at any time, with small check sizes.

They raised three funds ($137M, $137M and $200M) and even poached the great Elizabeth Weil, that I had the pleasure of meeting while at A16Z.

FundersClub

FundersClub is an online VC, as in they’re using network effects to run a centralized yet community-driven VC firm.

So, differently than AngelList, they actually have a FC portfolio. They don’t fund direct competitors, but pick one team to back per market opportunity, and then try to actively add value.

They’re also doing some interesting stuff with funds and partnerships.

Unshackled

Unshackled is a super smart arbitrage play. They market towards all the people that are stuck with US work visas or want to get to the US.

In exchange for equity, Unshackled not only provides cash but also acts as an employer and visa sponsor for founders. That’s gotta be genius.

Unshackled raised some $5 million from some 80 A-listers like Laurene Powell Jobs, Jerry Yang and Bloomberg’s venture arm. A larger financing round is said to be in the works.

Studios (Science, Expa, etc.)

The studio model has fascinated me for quite a while, and I even compiled a long list of them (which I’ve since stopped maintaining because every week there seems to be a new one).

It surely isn’t a new model (IdeaLab has been doing this forever), but more and more hybrid examples are launching and I think it’s worth to keep track of it.

If you’re able to make it work (it’s really hard), the economics can be absolutely amazing, as you end up owning a significant part of the company.

One of the newest interesting hybrids is Expa, which couples it studio activity with its venture investing and also acceleration program. Going full circle.

Vertical Funds (Seraphim Space Fund, Rock Health, etc.)

Again, not a specific fund here as much as the concept of a fund that focuses deeply on one vertical. We’ve seen with Data Collective that this can be done on a very broad horizontal theme, but oftentimes it can make solid sense to do it in a vertical market.

Obviously, the market needs to be absolutely gigantic, otherwise it becomes really hard, but given the right market the pros can fast outweigh the negatives.

In this regard, I think the performance of Rock Health (which started as an incubator) can be a very good example of the possibilities.

Scout Programs

The WSJ scoop on Sequoia’s scout program was a defining moment for me to understand the ambition and innovation of the best people in the business.

Sequoia clearly doesn’t need to differentiate in order to get fresh LP cash, as it can raise however much it wants.

But it surely still needs to make sure it’s always relevant and on top of what is happening in new areas.

The scout initiative was a really well played move, that’s been used by countless other VCs with varying degrees of success as we speak.

I hope that this list can be inspiring to current and future managers that want to bring some innovation to the VC landscape. If you’re exploring alternative and innovative models, I’d love to chat. You can find me on twitter here or via email.

Fundraising is supposed to be hard

As is running a startup

A day doesn’t go by where I don’t hear people saying that the fundraising process for startups is too cumbersome, hard to navigate for new entrants and inefficient.

I’ve raised $3.7M for my own company from top investors and invested in more than 40 companies by now, and I’ve come to form an opposing view: fundraising is supposed to be hard, and anything that makes it much easier introduces more risk in the ecosystem.

Having run a startup for a while, what I came to realize is that fundraising is actually the easiest part of running a company.

Hiring the best in class leaders, selling a half-backed solution, making a great product, navigating uncertainty, getting distribution and all of the other million tasks in the daily life of a startup founder, are all way harder than fundraising.

Additionally, most of those things have never been done or learned before by a startup founder, whose top quality should be learning fast while on the move.

Getting a warm intro, understanding how VC funds and partnerships work, what the process is like and what VCs expect of a startup founder, is the first big test to see if someone could ever even think of running a high-growth organization with big potential.

The counter argument usually used lies in the fact that VCs tend to fund people like them and people they know, but I find that to be rarely the case. In our portfolio we have entrepreneurs from a wide number of countries, races, sexual orientations, political opinions and religions. 95% of them we didn’t know before and few had friends in common with us.

Y Combinator and other very early stage efforts have leveled the playing field by giving everyone (who deserves it) an equal shot at starting a tech company. More efforts at this stage will always be very impactful as they put people who might be discriminated in different way on the same starting line, but after that meritocracy kicks in and founders need to demonstrate that they are up to the task for which they are asking other people’s money.

(edit: this has been sitting in my draft folder for a bit, and just noticed Marc Andreessen said something along the lines in his #startupschool talk).

Startups are a sport, and Silicon Valley is the Olympics

As everyone else, during the past weeks I’ve been watching the Olympic Games, and more than the results and medals, I was really trying to get to understand the lives of these athletes.

I’m fortunate to be close friends with two Italian team members and have a very real understanding of all of the sacrifices they made during the years: 5am wake ups, long trips, no social life, physical pain, financial stress, and the like.

I also understand how they were introduced to the sport by their family, their dad having won an olympic medal himself.

Drawing a parallel between the Olympics and the startup world.

Living in San Francisco for 5 years and being in close contact with very successful founders, employees and VCs, made me realize how their lives are similar to pro athletes.

When talking to entrepreneurs and other participants in the startup ecosystem in Europe, it seems to me that not everyone really grasps the difficulty of the startup game.

I suggest trying to think about startup founders as olympic athletes.

I see many people with absolutely no experience or no specific talent / expertise claiming that they can build something of immense value, and to me, that sounds like someone watching a 100m race and saying: “I like that, tomorrow I’ll start training and in a few years I’ll be at the Olympics”.

Now, I don’t want to say that it’s an impossible game, but I would really like more people to realize what it takes. And it takes talent, grit and ecosystems .

Talent

When we watch the Olympics we tend to overestimate natural talent and underestimate the training it takes to get to that level.

When we read about successful startup people instead, we tend to underestimate both the effort and the talent that it takes to get to the top.

Zuck, Travis, Ev, Marissa and everyone else we consider at the top is a star-performer just like Bolt, Phelps and Biles.

They have unfair natural talents that they coupled with insane amounts of work and focus.

As an aside, a very, very interesting short read/listen on the mix between talent and training is provided by NPR’s Hidden Brain podcast:

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/04/472162167/the-power-and-problem-of-grit

Grit

The reality is that the people we read about on Techcrunch and the likes, are the startup world’s top athletes and the sacrifices they make to reach that performance level are very similar to athletes’ ones.

If you want to create a hugely successful and valuable company, you must put in the hours and devote your life to this goal.

On this, I suggest listening to the end of this Twenty Minute VC podcast episode with Matthew Ocko:

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/04/472162167/the-power-and-problem-of-grit

His #1 tip? “Never sleep”

Ecosystem

Some teams from specific countries almost always tend to be on the top-3 in every single Olympic (eg. fencing for Italy). That’s usually the result of a lot of smart people working together to have that one or two athletes get the medals. Coaches, support staff, federal organizations, school teachers, everyone matters — and the highest concentration of smart and dedicated people, the better the results.

It’s the same with startups. Thinking about creating a massive startup outside of a solid ecosystem, while possible (as some independent or upcoming athletes have shown), is extremely hard and most definitely the exception rather than the rule.

Thinking about startup stars as olympic athletes and as myself as a training athlete really makes it easy to put in context the successes, sacrifices and ecosystems. It might be helpful for others too.

If your goal is to create hugely successful businesses (and it doesn’t have to be), then the reality is that it’s extremely hard, you need to get lucky with your natural talents and the environment you grow up in or surround yourself later in life, and put in insane amounts of work and focus.

Takeaways from YC’s Demo Day Pitches — from an alumnus turned investor

With every new demo day I see, I notice some more recurring themes and small optimizations that could be made to the pitches.

This is because I’ve attended many demo days: first as an investor, then as a founder (W15), and finally as an alumni/investor. I know what Demo Day means for both the founders and the investors given that with Mission and Market we’ve also already invested in 18 YC companies.

The pitches are superb, especially considering they are put together in the last few days, and these are just notes on the few things that I think could be improved. I hope they can be helpful and valuable for eventual W17 participants.

0. YC is scary good

This is another stunning batch. I’m still equal parts impressed and scared at YC’s sustained quality and incalculable ROI potential.

I’m equally more impressed at the genius of YCVC’s LPs who continue to get an index of YC companies at a great price with zero effort. Kudos 👏.

1. Mismatch between founders and investors perspective

As for fundraising itself, pitching presents a unique problem in the fact that an entrepreneur only needs to create 1 pitch, but an investor needs to sit through 100+. This creates a misalignment of incentives, perspective, information, and so on.

The founder wants to explain the key things and biggest achievements, and only really thinks about their pitch. But so does every other founder.

A founder thinks that as long as their pitch is good they’re golden, but the reality is that founders should pay a bit more attention to how all their batch-mates are presenting their companies — to really get a feel of what it could be like from an investor’s perspective.

As YC’s average company quality keeps on rising, it means that getting noticed becomes harder and harder, because having a big market, great traction and a good team are now just baseline.

An investor might sit there and see dozens of high-quality pitches that check all of the thesis / sector boxes, but will probably only invest in 1–5 companies.

2. No originality

As a result from the point above, this year too, most pitches are all the same.

Numbers, LOIs, revenue potential “from just these customers”, $B market, perfect team for it, and so on.

- What the founder thinks: this is awesome, ticks all the boxes, yay me!

- What the investor thinks: yawn, this is the 50th I see today that says the same thing.

The problem with non original pitches is that, for me, as soon as I start to get excited about one for some reason, I’ll kick myself and say: “why didn’t you get excited about the other 30 with the same exact numbers?” “maybe this is just baseline and none are exceptional”.

There is much more to gain than to lose from spicing up the pitch and trying something no one in the batch will.

Comedy, videos, animations, personal story references, whatever would usually be a total no-go for a pitch, become fair game when pitching as one of 100 others. (There’s the classic problem of needing to be the first and only to do it, because 100 animated pitches are obviously much worse than 100 normal speeches).

3. Unrealistic numbers

I clearly remember at my first investor demo day a company announcing they would be making an insane amount (9 or 10 figures) in revenues that same year.

Now, I’m sure we’ll see such a company in my lifetime, but it is extremely unlikely that a company would be pitching for an investment in front of investors if they’re going to make that cash.

This makes me discount all of the other things the company says + a lot of what the other companies will say.

In general, it’s really easy now for me to tell which numbers are genuinely true and which ones are only the result of a super-short unsustainable hustle that is clearly pre-PMF — as much so as I almost remove from the equation traction altogether at this stage.

4. Very early companies

I don’t know if there have been a lot of pivots during the batch or if there were a lot of very young companies accepted, but I’ve found a lot of companies saying “after just 2 months” etc.

This is making it obviously amazingly hard to judge any of these and justify the valuations. Eg. “if you’ve been able to do all of this in just two months, and there doesn’t seem to be any unfair advantage anywhere, maybe a lot of other people could do that too”.

5. Stories work, big numbers don’t

I have clearly noticed that the pitches I get mostly excited about don’t start by saying: “we have X customers and Y revenue, and there are Z addressable customers”, but are the ones that take time to explain the story. They get me interested in the market, team, solution — something.

I much prefer getting a glimpse of the vision and mission rather than a sterile recount of numbers.

6. Defensibility

As the startup market gets more and more crowded, something I worry about a lot is how defensible a technology, brand, market positioning, or whatever really can be.

It seems to me this is not addressed enough and sometimes might cause me to judge a company too quickly because I’ve either seen many other companies do the same thing or worry it can be replicated by great and fast companies in adjacent markets.

Imho, these would be wisely invested seconds.

7. no UA

I still don’t think I’ve heard from one company how they acquire customers. We certainly didn’t explain it in our pitch, and I regret it. But in today’s environment that is the #1 thing I think of and the easiest reason to dismiss something “cool, but how in the world are they going to consistently and profitably acquire customers at scale?”.

I know 2.5 minutes isn’t a lot of time to give a full picture of company, but 20 seconds to tell me about an edge acquiring customers can make all the difference.

Note:

- I unfortunately wasn’t able to attend live this year, so I watched all presentation videos online (thanks YC!). I must say that I have really enjoyed the confort of watching the videos from my own couch at my pace, researching the company and the founders online at the same time, while stopping and resuming. I also had the privilege of having my two partners at the event who could ask the questions that came up and round details which made it the perfect setup. I highly suggest it.)

Ideas aren’t worthless

I wrote this post years ago on my personal blog, but after having invested in ~40 companies (and raised a multi million $ seed round) I’m way more convinced about it and wanted to share it again here on Medium.

Let’s end this bullshit now. Ideas are not worthless. Ideas are important and the very foundation of every successful company.

TL;DR at the end.

The “ideas are worthless” mindset

I feel the industry is failing in messaging a very important point, and that is the fact that ideas are not the only thing in the success of a company. Being in love with the valley’s state of mind, I too have been drawn by this to think that ideas are worthless and execution is king. I actually believed this and told this to every founder that came in pitching their business while I was working in VC as well as almost everyone who asked for advice.

Well, turns out I was wrong. I’m sorry. Your idea was not worthless (even thought it was probably pretty bad).

It took me a while, but slowly I realized how broken this mindset is.

What is an idea?

It might help to define what we’re talking about.

I like to think about an idea as the sum of:

- finding a pain

- in a fast growing market

- hypothesizing a product or service solution

- and understanding how to bring it to your customers

So, for me at least, an idea is not: “hey, let’s build an app to get a black car”, but more of:

- getting a cab sucks

- transportation is enormous and people hate driving their cars around, parking is scarce and expensive

- the easiest thing to do is to work with black cabs

- we’ll build it as an app and get it to the tech elites in SF to make it look exclusive

It’s a story.

Do VCs value teams or ideas?

Valley VCs like to make you think that they only decide on investments based on the team, but in reality (consciously and unconsciously) what they are really valuing is a mix of factors, best represented by your idea (as defined above). The questions a VC asks and answers in his mind are along the lines of:

- does this make sense? Is there a real pain and opportunity? Is the solution smart? Will people use it?

- is there a big and growing market for this? if not, can it create a new market?

- is this the right team to execute on this idea?

You only get to the team part if the ideas makes sense and the market for it is huge. On top of that, you have to be the perfect fit for the idea you chose (right skills, unfair tech or knowledge advantage, etc.).

Only very few and very early investors can afford to invest based exclusively on the team (Y Combinator most of all), and are probably skewing the message that needs to pass to entrepreneurs.

When I raised my multi-million $ seed round, no one dug into the team’s expertise as deeply as they did into the pain, market, solution and customer acquisition strategies.

The canonical pushback on the argument that ideas are important is the following.

Ideas are cheap. What matters is execution.

Which I would rephrase as:

Bad ideas are cheap. Good ideas are extremely rare and executing them is incredibly hard.

Ideas are valuable. Good ideas are scarce.

And when an investor finds one, he’ll definitely get interested into it even if he’s never heard of the team. That doesn’t matter that he’ll be funding it or that it will work.

There’s one catch tho: evaluating ideas might be one of the hardest and most counterintuitive thing ever.

Paul Graham recently wrote:

“the best startup ideas seem at first like bad ideas. […] if a good idea were obviously good, someone else would already have done it. So the most successful founders tend to work on ideas that few beside them realize are good.”

Not many investors realize good ideas actually look pretty dumb in the beginning to people who still can’t connect all the dots together. That is as true as hard to admit for an investor, so big kudos to PG on that.

This is also the only reasonable counterargument to the “ideas are important” philosophy: “ideas are extremely hard to evaluate”. YC now actually lets you apply without an idea. Does this mean that ideas are worthless? No, it means that they are receiving a ton of bad ideas and want to make sure that good founders work on good ideas. So often smart investors will strip down the idea into its core parts of market, opportunity and solution and will evaluate on those before moving on to the team.

When is an idea good or bad?

At this point we should probably start to explore what makes an idea good and what makes it bad, cause this is where most of the confusion happens. But don’t hold your breath, I don’t really know. I like to think that you have a good idea when you have a good number of those elements:

- A deep understanding of something specific. An obsession.

- Knowing something is true that almost nobody agrees with you on (cit. Peter Thiel)

- The realization of a problem, gap in the market, future market shift

- A creative and innovative way of exploiting that knowledge

- A new enabling technology that dramatically lowers the barrier to creating something (better if proprietary)

- A marketing insight to get people to notice your product

- Some unfair competitive advantage and barrier to entry in respect to other competitors

A good idea is derived from spark, creativity, business acumen, luck, technical knowledge, madness, experimentation and sometimes laziness.

Wow cool, so that means I should ask everybody to sign an NDA before telling them my idea!

Not even in the slightest. Even tho ideas matter:

- execution is still what makes them successful

- you should have had the idea because you are passionate about the market and have either an obsession or deep knowledge that other people don’t so:

- other people will probably not think that your idea is good and thus:

- nobody will even consider copying your idea when they have an already long list of theirs to execute

- As a bonus, I’m a firm believer that you should be the right team for the right idea (probably another post about that too), meaning that anyone who copies your idea should fail. (They called this founder/product fit in the meantime)

But what about pivots? Every successful company pivoted from an original idea to something different!

You can’t pivot yourself from a stupid idea in a small market into a great one. Your original insight has to be a decent one first. you have to find the pain.

A pivot should come from a much better understanding of the market, the customers, the technology etc., and should be the ultimate good idea.

A pivot is not: oh photo sharing didn’t work so I’m going to do a subscription e-commerce for pets. And, as a bonus, a pivot is not: “oh podcasting didn’t work so let’s do status updates”, cause that should be phrased like “ok podcasting didn’t work, it was a bad idea because there was no market for it, let’s call investors and tell them they can take their money back or stick with us while we work on a new thing”. That’s not a pivot, but a new company entirely.

SHOCKER: most people invested in Twitter when it was already Twitter. And everyone invested in Facebook, Square, Evernote and Dropbox, when they were already working on the companies we know today.

Further awesome reading: The only thing that matters by Marc Andreessen (spoiler: it’s the market).

—

Happy to chat more about it on Twitter here

Why we need an alternative to venture capital

Having recently left San Francisco for the Italian alps, I have been reflecting a lot on the opportunities and problems for companies outside of startup hubs which, by the way, are the vast majority of the world’s companies.

In this post I’ll try to put down on virtual paper my current observations and the reasons I think there is a clear opportunity for alternatives to standard VC approaches at the moment and in the future.

The trends

1: VC isn’t for everyone.

Running a micro venture fund, I can more and more understand how VCs need huge outcomes to make any attempt at a decent return for their LPs.

The VC model makes it absolutely non-profitable to invest in any business which doesn’t have a very real chance of being a $100M+ business in a relatively short timeframe.

Oftentimes I’ve found myself saying:

wow, this is going to be an awesome business, but I seriously doubt it could scale past $5–10M in revenues.

If you think about it, that’s a crazy thing to say: an “easy” $5–10M business is amazing!

But the risk / reward balance is completely different from how we (and most VCs) set up our fund, where most businesses are expected to fail (because they risk big trying to become #1) and so the successful one needs to return the fund multiple times (eg return 50-100x).

This means that any business who structurally only has the possibility to become a $1M-$10M business, or is playing in markets who don’t enjoy massive margins and stellar growth, needs to find an alternative to finance itself.

And guess what, that’s 99% of all businesses in the world which are getting overlooked by VCs.

2: Growing trend of businesses aiming for healthy sustainability

Some savvy businesses now openly reject the VC-first, growth-at-all-costs mindset and intentionally go out to create a small, sustainable business that doesn’t drive them crazy.

This growing number of entrepreneurs is thinking very strategically about their funding options, and is not compromising on control of the company and dilution.

This is not only happening in not-sexy-anymore markets like retail, ecommerce, and services; but also more and more in traditional VC hotbeds like SaaS.

Building a 500+ person business or being the market leader in a category is not in the wildest dreams of most people. Most entrepreneurs start out wanting to bring something to the market and then use employees and growth as a tool to deliver a better product or service, while also making more money.

Most entrepreneurs are perfectly happy running a profitable business, which gives them a high quality of life and fulfills them.

3: Alternatives suck

So, we have VCs that rightly focus only on what will drive their very specific returns, but at the same time we would expect the market to take care of the remaining 99%.

Somehow that’s not the case. Financing a non-high growth business is a mess and business owners spend way too much time between bank loans, government programs, friends and family, reward crowdfunding, equity crowdfunding, etc

None of these options are easy to access, and most importantly none of these options are optimal for these businesses.

This means that these businesses also often go and try to raise money from traditional VCs and accelerators, wasting everyone’s time and creating a lot of discontent in the process: VCs are overloaded with mediocre “venture” deals, and entrepreneurs need to face multiple rejections (try hearing all over again “your business isn’t good/fast/big enough” multiple times per day) and end up spending a ton of time on activities which don’t contribute to the business.

As you can see from Frank Denbow’s post, it doesn’t look great for someone who wants to fund their business without venture capital. Especially if outside of the US.

There isn’t much for most small internet businesses that need an investment and which are somewhat risky (no bank loans), will only be able to return it in the medium term (no pure debt), and don’t have the possibility to become a $100M+ business (no venture capital).

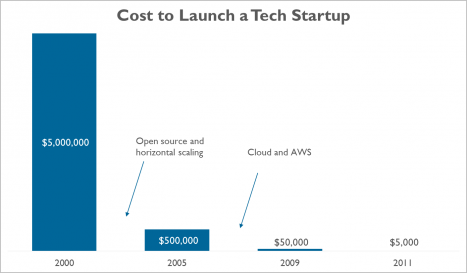

4(a): Plummeting cost of starting an internet-enabled business

Nothing new here: cloud, open source, great content, etc.

What is rarely mentioned is the, quite obvious, impact this has: many, many more internet companies are being created every single month.

4(b): It’s getting harder and more expensive (plus physically and mentally taxing) to become a gorilla business

Uber has famously raised $12.5B in funding, and doesn’t look like it’s done, in order to become the dominant player in its market. Many other venture businesses are following suit and are having to raise bigger and bigger rounds in order to keep the growth trajectory needed.

Increased number of companies means increased competition, which in turn leads to higher customer acquisition costs for virtually anyone, requiring more and more cash in order to grow big.

It’s not easy wanting to become a big startup when you start with 3 competitors with $20M in funding each. Take for example all the food ordering startups, or even the much more unproven market of “we’ll park your car for you in SF”.

VCs are also all trying to put the most cash possible into the few deals who will return the most money, meaning funding for non-category winners could be scarce.

4(c): Bigger and bigger online markets

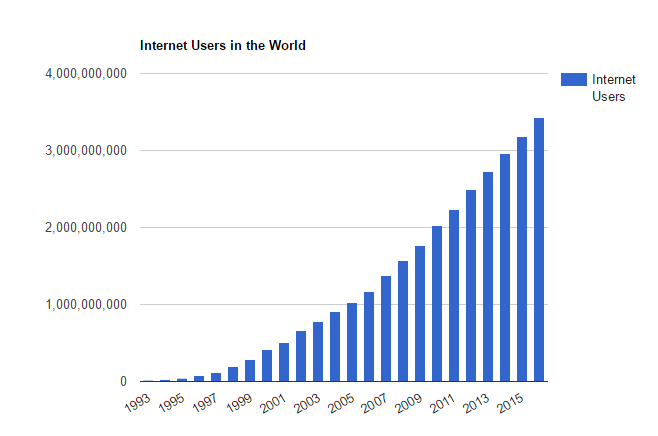

Again nothing new here, I could insert any other up-and-to-the-right graph in here to explain just how many potential buyers of products and services exist today online.

4(d): Increasing number of very successful niche businesses

The above points, mean that I believe we will continue to see more and more successful small internet businesses — which is an awesome thing.

These businesses will continue to enjoy the key traits of vc-funded internet businesses (high-margins, easy to distribute, scalable, easy to pivot and adapt to the market, etc.) but won’t have to compete to the extreme in order to become the dominant player in a specific market.

In fact, VCs’ biggest problem today isn’t finding which business will work and which won’t, but finding which business will scale and become massive.

Christoph Janz and Josh Hannah famously wrote that building a $1–2M SaaS business and a $10–20M ecommerce business is not that hard.

5: Not everyone can be located in a startup hub

Creating a high-growth startup outside of the traditional startup hubs adds another (big) layer of difficulty to achieving unicorn status.

Local VCs can surely fill the gap, but oftentimes it’s not particularly profitable to set up a VC fund in non-hot ecosystems which leads to scarcity of venture capital. Italy is a prime example of this.

The opportunity

Given all of the above, I think there is a clear opportunity for creating alternative financing programs that target this emerging crop of successful, profitable, quality businesses which I like to call SIB (small internet businesses).

I think the bulk of businesses that would be interesting candidates will fit in the three very broad categories of ecommerce, saas and services; and will exclude anything that is social, consumer and big tech; but I won’t be surprised to find unexpected business types in the mix.

I’m still figuring out what the perfect instrument would look like. It will most likely have to be a mix of equity, convertibles, pure debt, royalties, preferred dividends, and other exotic structures.

Who’s doing something about it

There are dozens of new venture funds launched each month, but surprisingly there aren’t many people tackling this new opportunity.

The one that drew the most attention recently is Bryce Roberts’s Indie.vc effort which started out as an experiment but has since raised a “big” dedicated fund to continue on the vision. They recently got a feature on the WSJ as well.

Indie.vc works in a very, very, very entrepreneurial friendly way: as soon as a company decides to pay a dividend, Indie.vc receives 80% of it until they get 2x their investment, after which point they will get 20% until a 5x return.

If a company decides to raise follow on funding or sell the company before they have returned the 5x, the investment will convert to a negotiated equity amount.

This model is very innovative and seems to have stirred up the interest of many entrepreneurs.

It remains to be seen how this translates to returns. 5x is not that much of a return, meaning that the margin of error in selecting the companies is very small and they can’t afford many to fail, otherwise they wouldn’t even be able to return the capital, let alone an interesting IRR (given that the return is also probably going to take a while).

That being said, Bryce has been thinking about this more than anyone else and already have a full batch of data to evaluated what would work best.

Others include Lighter Capital, which loans between $50,000 and $2M and gets repaid through a percentage of the company’s revenue. This approach is a mix. On one side, it can be considered less entrepreneurial-friendly and aligned to the company, as it takes away very valuable money from the company’s balance sheet, especially if still unprofitable.

On the other side, the business won’t give away any equity should it get acquired or raise more money, Lighter is incentivized to have the business grow faster, and the maximum repayment will be around 1.2–1.8 times the investment.

RevUp by Betaspring has the same model, but act as an accelerator program at a much earlier stage.

As I enter the next dimension of my life outside of a startup hub, I’m extremely interested in understanding how this growing number of businesses can be financed to enable more innovation, economic growth, job creation and ultimately value creation in places that can’t rely on billion dollars venture funds.

If you have any thoughts, I’d love to hear them. And if you’re going to be at Microconf Europe in Barcelona, I’d love to chat about it there!

p.s. I’m still very bullish on the venture capital business model for high-growth companies located in startup hubs and I’m still investing out of Mission and Market in such companies out of San Francisco, like our portfolio companies Eaze, Padlet, Transcriptic and more.

We’re specifically looking at any company that can leverage proprietary deep learning techniques to create previously unimaginable value and efficiency such as our portfolio companies Atomwise and Enlitic.

What it takes to start your own venture capital fund

It seems that becoming a VC is a dream of many, and rightly so: it’s really a fantastic job.

As a venture capitalist, you’re paid to learn as much as possible about new markets and to meet with the smartest people you can find. You get to follow along the entrepreneurial journeys of founders much smarter, determined and audacious than you are, without the massive amount of risk of having all your assets and a lot of your professional reputation tied to a single outcome. That seems like a dream job description to me.

Working as a VC associate right after school, I really got spoiled and so after 3+ years in an operational role at a startup, I decided I wanted to start investing again.

There were just a couple of problems:

- I did not have any money whatsoever to invest

- It was highly probable that no VC firm would have hired me as anything more than an associate

- I had an idea I was deeply passionate about and wanted to bring to reality:

While talking with my friend, he started suggesting we start our own fund and run it part time as “angels”.

I obviously thought he was crazy.

But dozens of espressos later, he had convinced me.

We came up with the idea of allowing our friends who are living in Europe to get exposure to the asset class of silicon valley startups.

The first person we pitched, gave us a resounding no. Not because he didn’t want to invest, but because he wanted to join our crazy adventure, and so over breakfast Mission and Market was born.

I get asked by a lot of people how they can get into venture capital. The answer is that it’s not easy given that jobs in the industry are scarce and usually reserved for people with a very specific background.

So, after having invested in more than 30 companies including Eaze and Transcriptic, I thought it might be helpful to explain what we did and why, and give a rough framework for people who want to get into venture capital by themselves.

HOW TO START YOUR OWN FUND

These thoughts are meant for people who want to start a small fund. If you’re starting a 10M+ fund, most of the below won’t apply!

1. Commit mentally

Talk to people who’ve done it before. I reached out to Semil, Zac and Shruti to understand what they did and how, and it was super helpful.

Be sure that you’re ready to commit to this for a long time.

2. Do the math!

RETURNING A FUND IS HARD!

There is plenty of money floating around startups and (as this post demonstrates) it is fairly easy to become an investor.

This means that the gold mines are getting crowded and the chances of finding that big nugget are getting slimmer. Fortunately for us, startups are not a non-renewable asset like gold, so if you put in time, effort and get a bit of luck, it still is very possible to generate meaningful returns.

But going at it without modeling out all possible scenarios is not a good idea. The math will inform a number of key decision you need to make:

- how many deals you want to make.

- what check size you’ll be writing.

- how much of the fund you will be reserving for follow on investments.

- how many follow-ons you’ll be able to do and the amounts.

Doing the math will also show you how much enterprise value you’ll have to generate in order to return the fund, and how entry valuations will impact this.

In our case, we’re aiming to make 60 investments out of our first fund. That means investing $1.5M in first checks, and then keeping what’s left (~ $1M) for follow on investments.

The reason to make 60 investments is simple: building a highly diversified portfolio is key to having a higher chance of funding one “unicorn”, which means better returns and better brand, which leads to better dealflow, and circularly to better returns (even for potential future funds).

We’ve done 30 in our first year, and will be making 30 more in the following 1.5–2 years, and then will just use the remaining capital to continue investing in the winners.

3. Define your compensation

Given we’re doing this part-time, we decided to not take any management fee out of the fund.

By doing this on a $2.5M fund, you are deciding to use the $50k a year in fees to make more investments and have a higher chance to provide solid returns to your investors. Incentives are also much more aligned.

If we had taken out the fees, over 10 years we could have drown $500k. That’s insane. It’s one fifth of the full fund gone. So now, you need to return a multiple of a $2.5M fund, but with only $2M to invest.

Our compensation is fully based on carry, and only kicks in after we’ve returned the full amount invested first. After that, we start sharing 20% of the returns. If we double our investors’ money, then we receive 30% of the following profits.

Do not expect to get rich out of this.

Say we return 3x our fund, $7.5M. That translates to $2.5M * 20% + $2.5M * 30% = $1.25M. Divided by 3 people that’s $400k, and divided by 10 years, that’s 40k/year. We could all get $40k more a year just by switching jobs.

And that’s assuming you return 3X the capital!

4. Find a solid team.

You can go at it by yourself, like Semil did, but if you want to do this while still working at a company or even running yours, it’s pretty mandatory that you join in with one or two other people.

If you think you have what it takes to go at it alone, you’re better off angel investing or doing syndicates over AngelList. Raising and running a fund is a lot of work, and should only be done if you have the time and flexibility to do it.

It’s very important to choose people that you like A LOT.

Choosing partners for a fund is even more critical than choosing a co-founder, as you’re actually writing down on contracts that you’ll work together for 10 years minimum.

It’s also pretty important to choose very smart people with a solid network and flawless reputation. Investing experience is the least of the concerns.

Francesco and Simone are the two best people I could have started this with!

5. Define your thesis and value propositions.

A thesis is not only what you’ll invest in, but in my opinion should also include the reasons you’ll do what you’ll be doing.

As an investor, you have two customers: your LPs (which act as both customers and bosses) and the entrepreneurs.

Our value proposition to LPs is access to a diversified portfolio of SF/SV-based startups with a small sum of money, which would be impossible to achieve by direct investment. European investors don’t tend to have much access to funds or startups, other than what they can do on AngelList and so it’s been a fairly easy sell.

Because of that, we don’t need a very specific thesis about the type of investments that we look at (other than the fact that they should be local to the Bay Area).