I wrote this post years ago on my personal blog, but after having invested in ~40 companies (and raised a multi million $ seed round) I’m way more convinced about it and wanted to share it again here on Medium.

Let’s end this bullshit now. Ideas are not worthless. Ideas are important and the very foundation of every successful company.

TL;DR at the end.

The “ideas are worthless” mindset

I feel the industry is failing in messaging a very important point, and that is the fact that ideas are not the only thing in the success of a company. Being in love with the valley’s state of mind, I too have been drawn by this to think that ideas are worthless and execution is king. I actually believed this and told this to every founder that came in pitching their business while I was working in VC as well as almost everyone who asked for advice.

Well, turns out I was wrong. I’m sorry. Your idea was not worthless (even thought it was probably pretty bad).

It took me a while, but slowly I realized how broken this mindset is.

What is an idea?

It might help to define what we’re talking about.

I like to think about an idea as the sum of:

- finding a pain

- in a fast growing market

- hypothesizing a product or service solution

- and understanding how to bring it to your customers

So, for me at least, an idea is not: “hey, let’s build an app to get a black car”, but more of:

- getting a cab sucks

- transportation is enormous and people hate driving their cars around, parking is scarce and expensive

- the easiest thing to do is to work with black cabs

- we’ll build it as an app and get it to the tech elites in SF to make it look exclusive

It’s a story.

Do VCs value teams or ideas?

Valley VCs like to make you think that they only decide on investments based on the team, but in reality (consciously and unconsciously) what they are really valuing is a mix of factors, best represented by your idea (as defined above). The questions a VC asks and answers in his mind are along the lines of:

- does this make sense? Is there a real pain and opportunity? Is the solution smart? Will people use it?

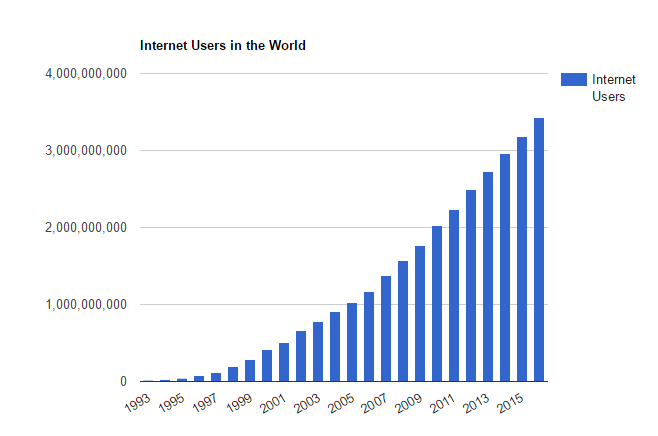

- is there a big and growing market for this? if not, can it create a new market?

- is this the right team to execute on this idea?

You only get to the team part if the ideas makes sense and the market for it is huge. On top of that, you have to be the perfect fit for the idea you chose (right skills, unfair tech or knowledge advantage, etc.).

Only very few and very early investors can afford to invest based exclusively on the team (Y Combinator most of all), and are probably skewing the message that needs to pass to entrepreneurs.

When I raised my multi-million $ seed round, no one dug into the team’s expertise as deeply as they did into the pain, market, solution and customer acquisition strategies.

The canonical pushback on the argument that ideas are important is the following.

Ideas are cheap. What matters is execution.

Which I would rephrase as:

Bad ideas are cheap. Good ideas are extremely rare and executing them is incredibly hard.

Ideas are valuable. Good ideas are scarce.

And when an investor finds one, he’ll definitely get interested into it even if he’s never heard of the team. That doesn’t matter that he’ll be funding it or that it will work.

There’s one catch tho: evaluating ideas might be one of the hardest and most counterintuitive thing ever.

Paul Graham recently wrote:

“the best startup ideas seem at first like bad ideas. […] if a good idea were obviously good, someone else would already have done it. So the most successful founders tend to work on ideas that few beside them realize are good.”

Not many investors realize good ideas actually look pretty dumb in the beginning to people who still can’t connect all the dots together. That is as true as hard to admit for an investor, so big kudos to PG on that.

This is also the only reasonable counterargument to the “ideas are important” philosophy: “ideas are extremely hard to evaluate”. YC now actually lets you apply without an idea. Does this mean that ideas are worthless? No, it means that they are receiving a ton of bad ideas and want to make sure that good founders work on good ideas. So often smart investors will strip down the idea into its core parts of market, opportunity and solution and will evaluate on those before moving on to the team.

When is an idea good or bad?

At this point we should probably start to explore what makes an idea good and what makes it bad, cause this is where most of the confusion happens. But don’t hold your breath, I don’t really know. I like to think that you have a good idea when you have a good number of those elements:

- A deep understanding of something specific. An obsession.

- Knowing something is true that almost nobody agrees with you on (cit. Peter Thiel)

- The realization of a problem, gap in the market, future market shift

- A creative and innovative way of exploiting that knowledge

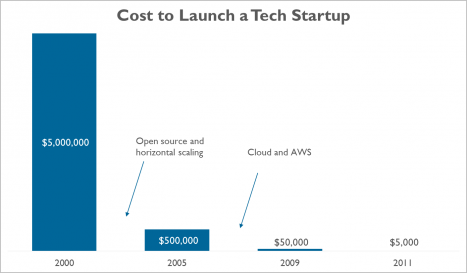

- A new enabling technology that dramatically lowers the barrier to creating something (better if proprietary)

- A marketing insight to get people to notice your product

- Some unfair competitive advantage and barrier to entry in respect to other competitors

A good idea is derived from spark, creativity, business acumen, luck, technical knowledge, madness, experimentation and sometimes laziness.

Wow cool, so that means I should ask everybody to sign an NDA before telling them my idea!

Not even in the slightest. Even tho ideas matter:

- execution is still what makes them successful

- you should have had the idea because you are passionate about the market and have either an obsession or deep knowledge that other people don’t so:

- other people will probably not think that your idea is good and thus:

- nobody will even consider copying your idea when they have an already long list of theirs to execute

- As a bonus, I’m a firm believer that you should be the right team for the right idea (probably another post about that too), meaning that anyone who copies your idea should fail. (They called this founder/product fit in the meantime)

But what about pivots? Every successful company pivoted from an original idea to something different!

You can’t pivot yourself from a stupid idea in a small market into a great one. Your original insight has to be a decent one first. you have to find the pain.

A pivot should come from a much better understanding of the market, the customers, the technology etc., and should be the ultimate good idea.

A pivot is not: oh photo sharing didn’t work so I’m going to do a subscription e-commerce for pets. And, as a bonus, a pivot is not: “oh podcasting didn’t work so let’s do status updates”, cause that should be phrased like “ok podcasting didn’t work, it was a bad idea because there was no market for it, let’s call investors and tell them they can take their money back or stick with us while we work on a new thing”. That’s not a pivot, but a new company entirely.

SHOCKER: most people invested in Twitter when it was already Twitter. And everyone invested in Facebook, Square, Evernote and Dropbox, when they were already working on the companies we know today.

Further awesome reading: The only thing that matters by Marc Andreessen (spoiler: it’s the market).

—

Happy to chat more about it on Twitter here